Anti-Apartheid Movement: Legislation

Read about the important role of CBC members in dismantling the apartheid system of South Africa.

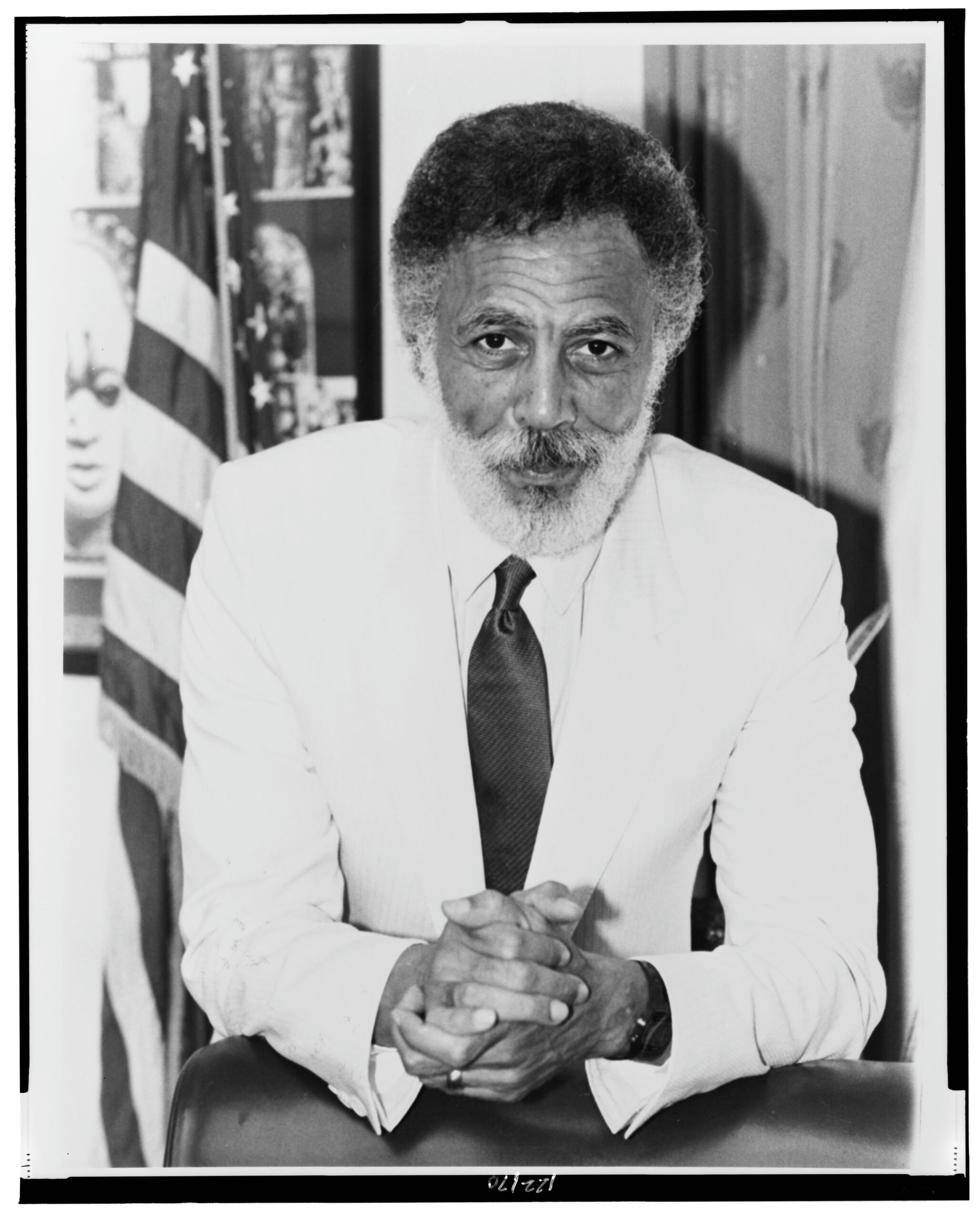

Rep. Ronald V. Dellums (D-CA)

Representative of California’s Eighth Congressional District from January 3, 1971 to February 6, 1998 (92nd-105th Congresses)

Shortly after its inception in 1971, the Congressional Black Caucus began the fight against apartheid. In 1972, Representative Ronald V. Dellums (D-CA) sponsored the CBC’s first bill concerning apartheid. The bill established the CBC’s position on apartheid and expressed the CBC’s support for the struggle of black South Africans. CBC members continued to introduce legislation that was designed to pressure South Africa into abandoning its racist apartheid policies. Congressman Dellums led this charge, sponsoring and co-sponsoring bills over the course of the next fourteen years. At the same time, CBC members worked alongside colleagues inside the House and with members of other organizations to bring national and global attention to the atrocities of apartheid.

A major concern of the Congressional Black Caucus was the important financial relationship between the United States government and the South African government. In 1985, Representative William H. Gray (D-PA), chairman of the Committee on Budget, introduced H.R. 1460, a bill that prohibited loans and new investment in South Africa and enforced sanctions on imports and exports with the nation. This bill also introduced sanctions on Rhodesia, United States business involvement in South Africa, and political repression in the region.

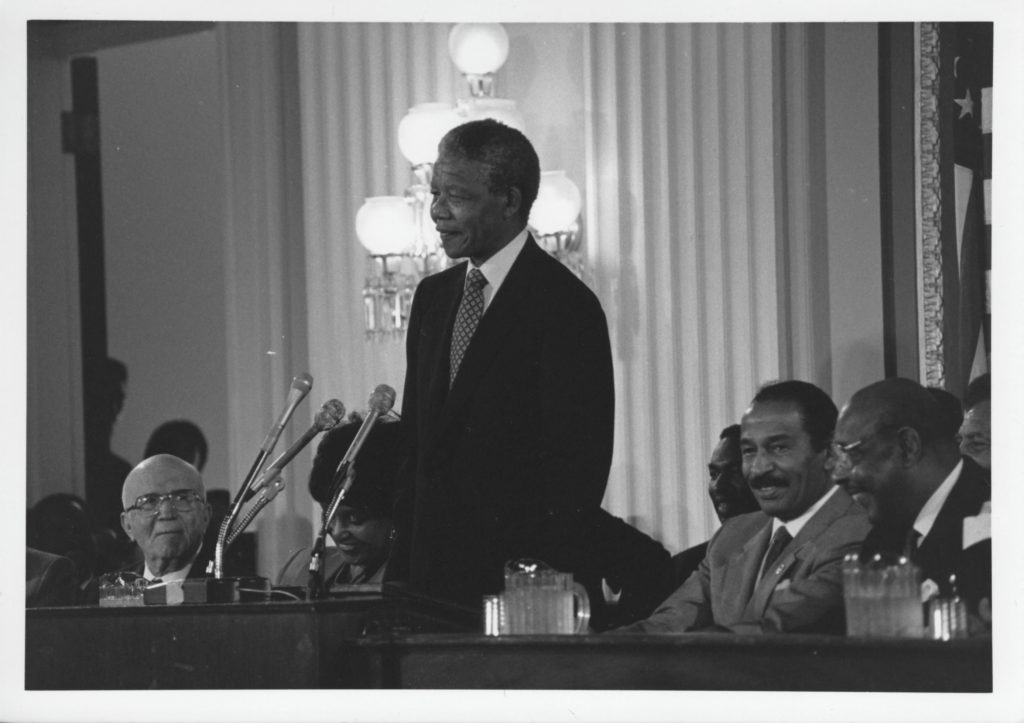

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 (H.R. 4868) became Public Law 99-440 on October 2, 1986. This legislation called for sanctions against South Africa and stated preconditions for lifting the sanctions, including the release of all political prisoners. (Among these political prisoners was Nelson Mandela.) Later that year, President Ronald Reagan attempted to veto the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, but was overridden. This override marked the first time in the 20th century that a president had a foreign policy veto overridden.

Two years later, Congressman Dellums introduced a bill to prohibit investments in, and certain other activities with respect to, South Africa. The House incorporated this measure as an amendment to the Comprehensive Act of 1986. Following the passage of this legislation, CBC members continued to co-sponsor bills to ensure the full implementation of the provisions of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.