Anti-Apartheid Movement: History

Read about the important role of CBC members in dismantling the apartheid system of South Africa.

Rep. Charles C. Diggs Jr. (D-MI)

Representative of Michigan’s 13th Congressional District from January 3, 1955 to June 3, 1980 (84th-96th Congresses)

African American interest and activism in the anti-apartheid movement began decades before Congress finally passed the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986. Likewise, the history of black congressional involvement in the anti-apartheid movement predates the formation of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) in 1971. However, the movement holds great significance in both the CBC and American history because it firmly established the voice of the black community in United States foreign policy.

In 1959, Representative Charles C. Diggs Jr. of Michigan became the first black chairman of the House Subcommittee on Africa. In this role, Diggs used the subcommittee as a place to raise the interest and levels of awareness concerning the political and social situation in southern Africa. The subcommittee was also a driving force in the mobilization of anti-apartheid activists in the United States. Its hearings on South Africa provided an important forum for discussing alternatives to existing United States policy, and it gave a platform to Africanists (African activists) and black Americans to raise their concerns.

When the Congressional Black Caucus was established in 1971, apartheid was a major policy concern. The CBC’s first bill concerning apartheid was introduced by Representative Ronald V. Dellums (D-CA) in 1972. The purpose of the bill was to establish the CBC’s position on apartheid and to end apartheid and other racist practices in South Africa. Although it would be at least another decade before the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act finally passed in Congress, CBC members proposed at least 15 bills that sought to pressure South Africa into abandoning apartheid.

During the 1970s, the influence of the Congressional Black Caucus on U.S. foreign policy was evident. In a speech delivered to the State Department in 1975, Congressman Andrew Young of Georgia advocated that the tactics used in the civil rights struggle in the United States should be used in South Africa. His activism continued when President Jimmy Carter appointed him as permanent representative to the United Nations in 1976. A year later, the CBC was involved in the establishment of TransAfrica, a foreign policy advocacy organization designed to force attention on issues concerning Africa and the Caribbean. Upon its establishment in 1977, TransAfrica immediately began mobilizing opposition to U.S. support of apartheid. The anti-apartheid movement resulted in some 5,000 Americans being arrested for protesting in front of the South African Embassy. It also led to a heightened awareness among Americans of the atrocities of apartheid. The movement to divest, or cease to invest or have operations, in South Africa, which was spearheaded by the black community, forced scores of universities and businesses to withdraw investment dollars from South Africa.

In 1985, Representative William H. Gray (D-PA), chairman of the Committee on Budget, introduced H.R. 1460, a bill that prohibited loans and new investment in South Africa and enforced sanctions on imports and exports with the nation. This bill introduced sanctions on Rhodesia, United States business involvement in South Africa, and political repression in the region. In 1986, Representative George Crockett of Michigan sought unsuccessfully to get the House to approve a resolution calling on South Africa to free Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners, and to recognize the African National Congress as the legitimate representative of the country’s black majority. While these efforts were initially unsuccessful, participation in the House-Senate conference on the sanctions and legislation against South Africa eventually led to the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.

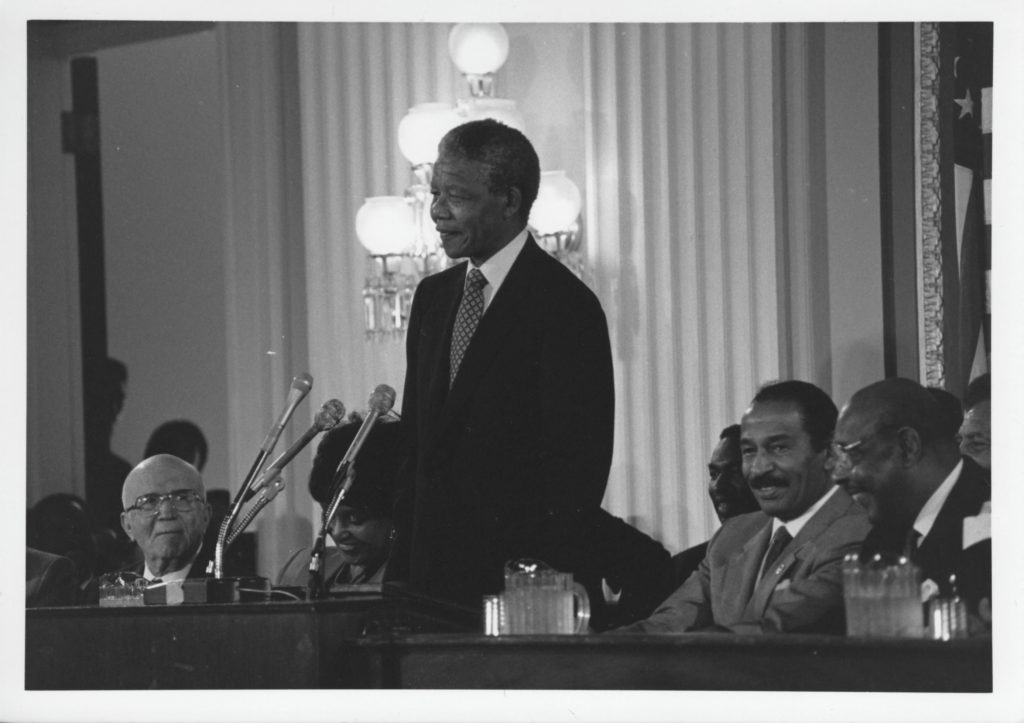

Nearly fourteen years after Representative Dellums’ initial bill, the U.S. House of Representatives passed anti-apartheid legislation, calling for a trade embargo against South Africa and immediate divestment by American corporations. In 1986, the bill was finally agreed to by both Houses of Congress. Known as The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, the bill called for sanctions against South Africa and stated preconditions for lifting the sanctions, including the release of all political prisoners. (Among these political prisoners was Nelson Mandela.) Support for the Dellums bill was so strong that it withstood a veto by President Reagan—the first time in the 20th century that a president had a foreign policy veto overridden.

The Anti-Apartheid Act triggered sanctions in Europe and Japan and the loss of confidence by the global banking community in the economy of South Africa. The CBC was instrumental in bringing an end to South Africa’s apartheid system. These days, the CBC continues to bring issues of human rights and equality to the forefront of U.S. foreign policy concerns.