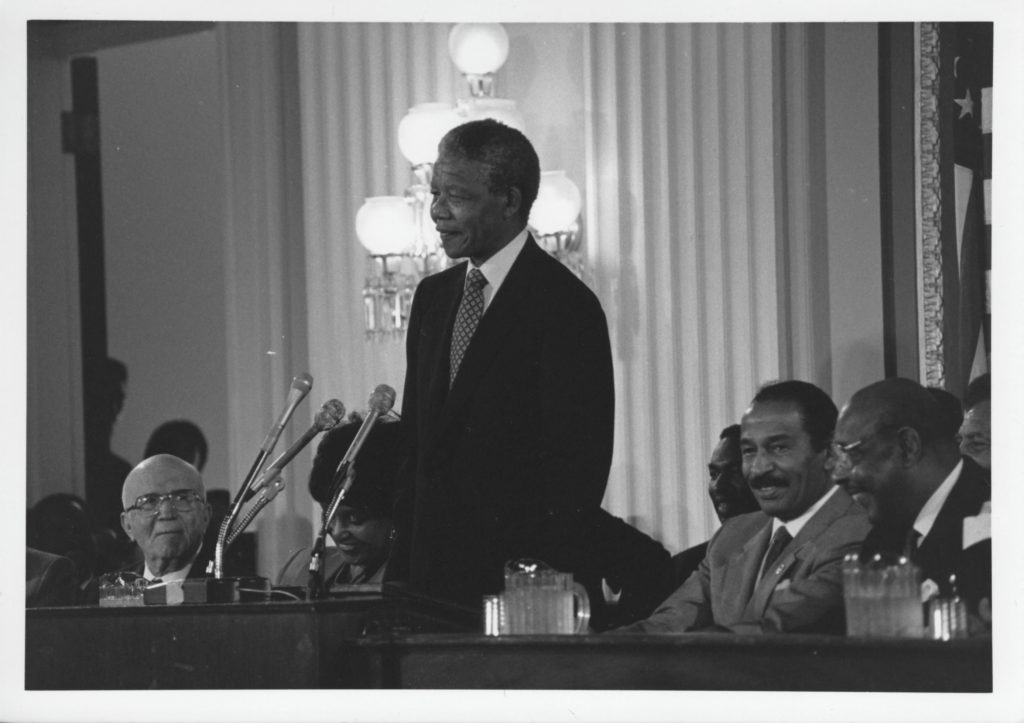

Anti-Apartheid Movement: Debates

Read about the important role of CBC members in dismantling the apartheid system of South Africa.

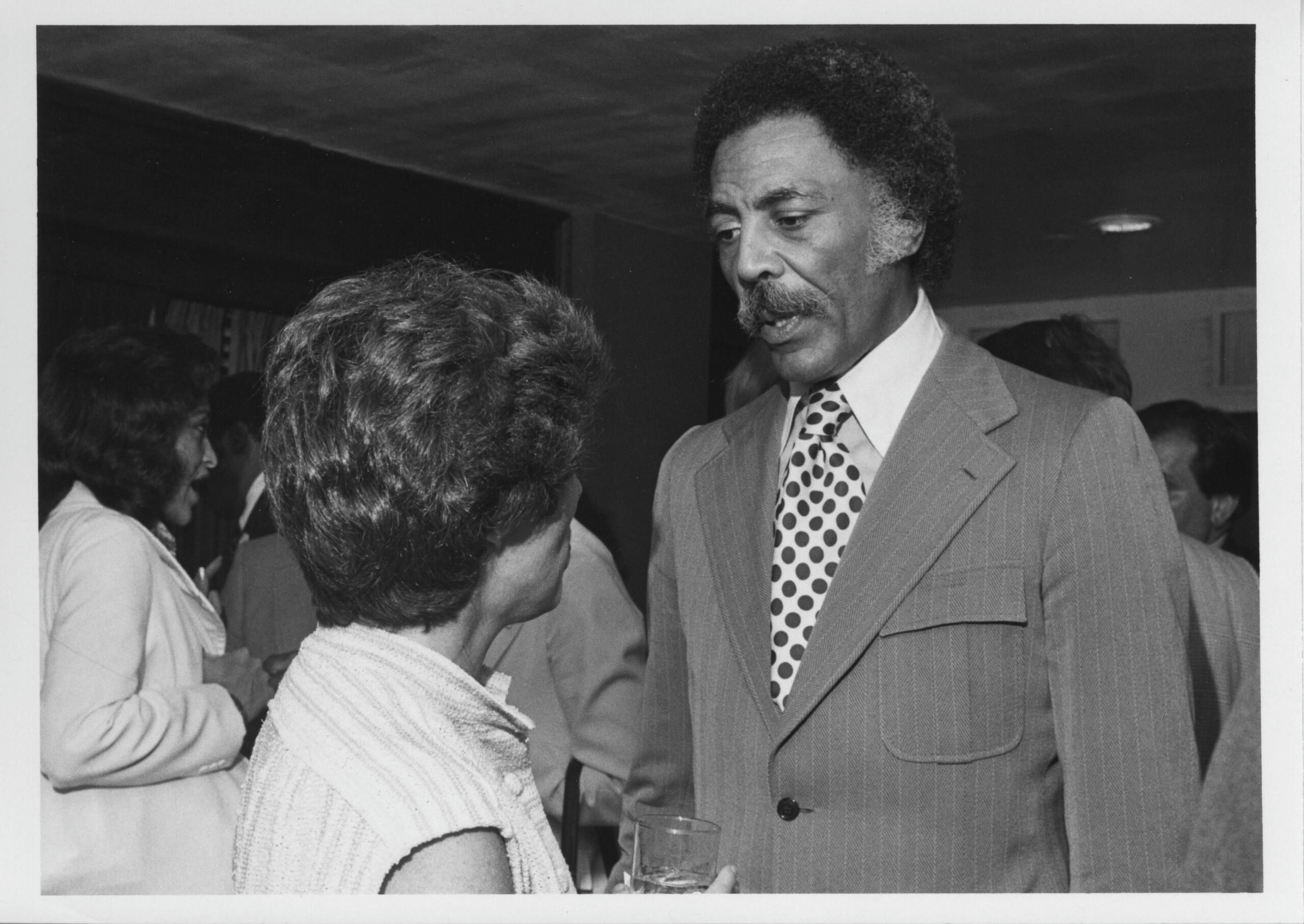

Rep. Ronald Dellums (D-CA)

Representative of California’s 8th Congressional District from January 3, 1971 to February 6, 1998 (92nd-105th Congresses)

In 1972, Representative Ronald V. Dellums (D-CA) sponsored the CBC’s first bill concerning apartheid. The purpose of the bill was to establish the CBC’s position on apartheid and to encourage the end of the policy and other racist practices in South Africa. CBC members expressed their support for the struggle of black South Africans and their extreme opposition to the apartheid system through the introduction of more than 15 bills that sought to pressure South Africa into abandoning its racist practices.

CBC members debated on the House and Senate floors, calling for a U.S.-South African policy of sanctions and economic disengagement – reminding Congress of the tremendous financial support that the United States gave to the South African government. CBC members recognized that because of its corporate and government involvement, the United States provided the financial fuel for the apartheid system. Although most agreed with the fact that the apartheid system was deplorable, a policy of economic disengagement was sharply contested. Opponents of this policy argued that divestment in Africa would be as detrimental to black South Africans as the existing system. CBC members defended the proposed U.S.-South African policy, recognizing the success of other economic sanctions. After extensive debate, the bill finally passed on October 2, 1986.

Following the passage of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, President Reagan attempted unsuccessfully to veto the legislation, stating that, “While we vigorously support the purpose of this legislation, declaring economic warfare against the people of South Africa would be destructive not only of their efforts to peacefully end apartheid, but also of the opportunity to replace it with a free society.”

Fortunately, support for the bill was so strong that it withstood a veto by President Reagan. This was the first time in the 20th century that a president had a foreign policy veto overridden.