Criminal Justice: Debates

Discover the history of CBC activism on criminal justice issues including police brutality, drug trafficking, sentencing and prison reform.

Rep. John Conyers Jr. (D-MI)

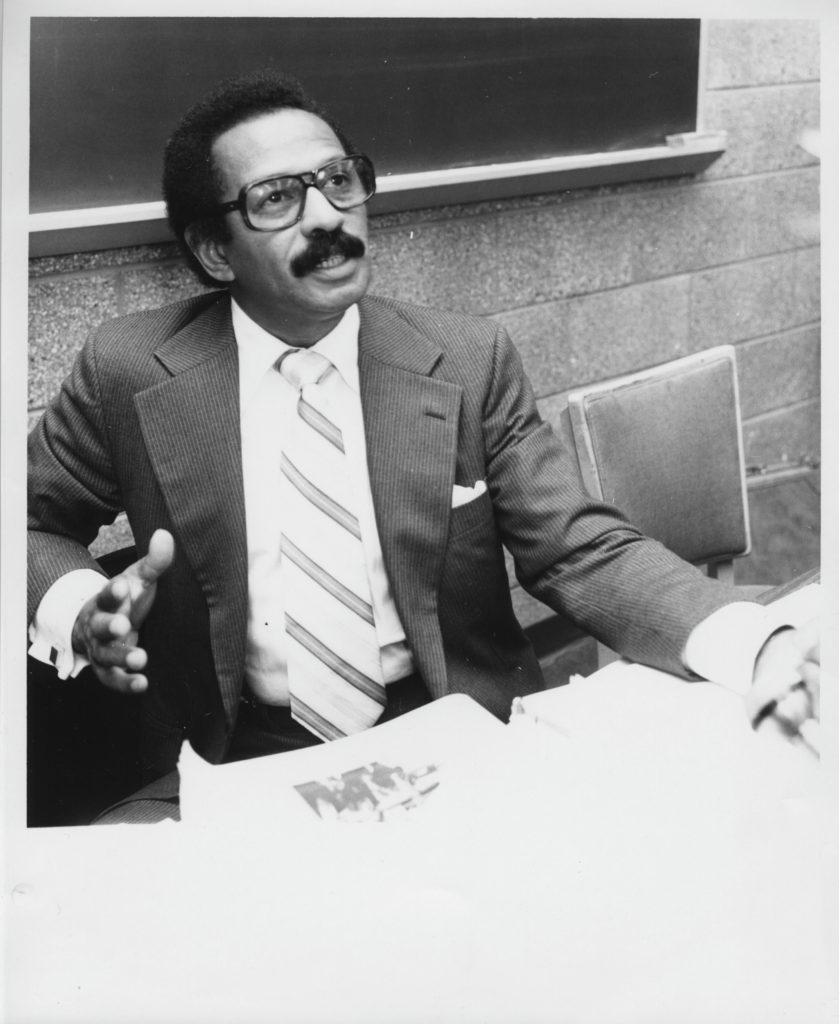

Black members of Congress have long been active participants in debates over criminal justice reform in Congress. Prior to the official formation of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) in 1971, Black congressional members like Reps. Augustus “Gus” Hawkins (D-CA) and John Conyers (D-MI) challenged the fairness of the nation’s most significant criminal justice laws. An early example was Rep. Conyers’ opposition to the DC Crime Bill, first introduced in 1963. Rep. Conyers recognized the negative implications of the legislation for the District’s Black community and its potential national impact. He argued the bills call for an expansion of police power over District citizens and introduction of mandatory minimum sentences would “act to the detriment of what the proposers of the bill [we]re trying to achieve – a crime-free city.” Despite recent civil rights advancements of the time, police brutality towards Black Americans was still a reality, and Rep. Conyers was wary of giving more power to police officers. In a floor debate opposing the bill, Rep. Conyers concluded with the following: “[t]his bill is a repressive and unpalatable measure, whether considered section by section, or as a whole. If it were adopted for the District of Columbia, it would undoubtedly serve as a precedent and pattern for the enactment of similar legislation by State and municipal legislative bodies.” So, when the Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice Assistance Act of 1967, also known as the Omnibus Crime Bill, was introduced, which outlined similar directives to give State and local governments more authority and autonomy over its procedures, Rep. Conyers voted against the bill, both in 1967 and upon its reintroduction in 1968.

Debates on the floor and within the CBC would continue through the mid- to late-1980s, as President Ronald Reagan sought to make his own contributions to drug and crime policies in America. A decade earlier, President Richard Nixon had declared the “War on Drugs,” but the drug policies and “Just Say No” campaign of the Reagan years proved a critical turning point for the American criminal justice system. Like many, Reps. Charles Rangel (D-NY) and Mickey Leland (D-TX) believed the campaign had been largely effective across the nation, but other CBC members, like Rep. George Crockett Jr. (D-MI), believed otherwise. In a statement on April 28, 1988, Rep. Crockett said, “Studies have shown that [the Just Say No’ campaign] is having some effect in lowering drug use. However, this success is solely among middle-class, educated young people…. The ‘Just Say No’ campaign is not working, however, and cannot work, with poor or educationally disadvantaged young people. These children DON’T see a bright future that will be threatened by drug use.” Rep. Crockett became the first of the CBC members, and of the Congress for that matter, to suggest a seemingly radical proposition for drug reform during that time: decriminalizing drugs. Doing so, he believed, would remove the profit motive and curb some of the nation’s drug problems. Rep. Rangel, who was also chair of the House Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control at the time, fiercely disagreed, stating that suggesting such a policy change would represent “moral and political suicide.”

President Reagan’s signature of the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 signaled a fundamental shift in crime policy. Under these piece of legislation, harsher mandatory minimum sentencing laws were instituted and consequences for engaging in drug activity changed from being more rehabilitative to more punitive. There was little debate at the time these laws were passed, including within the CBC. As years past, however, the CBC began to see the damaging effects of these policies, namely the significant increases in incarceration of Black young men due to harsher sentencing for drug offenses involving crack cocaine versus powder cocaine. In addition to introducing legislation to address this disparity, CBC members often took to the floor to call attention to the issue.

CBC members expressed mixed responses to President Bill Clinton’s signature of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act (“Clinton’s Crime Bill”) in September of 1994. As one of the largest crime bills in United States history, it channeled billions of dollars to pay for new police officers, fund prisons, and increase funding for prevention programs, but more importantly, it expanded federal law in areas ranging from death penalty and civil rights-related crimes (hate crimes and sex crimes) to gang-related crimes. The CBC advocated for the bill to contain the Racial Justice Act; legislation originally proposed by Rep. Conyers in 1988 to allow those convicted in capital cases to appeal their death penalty based on their ability to show racial disparity in their sentencing. When the final version of the bill did not contain the racial bias provisions, the CBC split. Despite the omission, a majority of the Caucus’ 38 members voted in support of the bill to secure the legislation’s other anti-crime provisions and, in the process, provided the necessary votes for its passage.

Debating key criminal justice reform issues on and off the House floor was not always easy, but there were instances in which doing so proved fruitful. Despite contentions within the CBC on Clinton’s Crime Bill, there was an almost unanimous sentiment against the drug policies of the Reagan era. CBC members, including Rep. Conyers, John Lewis (D-GA), Floyd Flake (D-NY), Maxine Waters (D-CA), and Robert C. “Bobby” Scott (D-VA) fervently debated the inequities of Reagan’s drug policies and worked to propose solutions. The passage of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, introduced by Rep. Scott, was a significant victory, but the debate surrounding fair sentencing issues continues in Congress today.

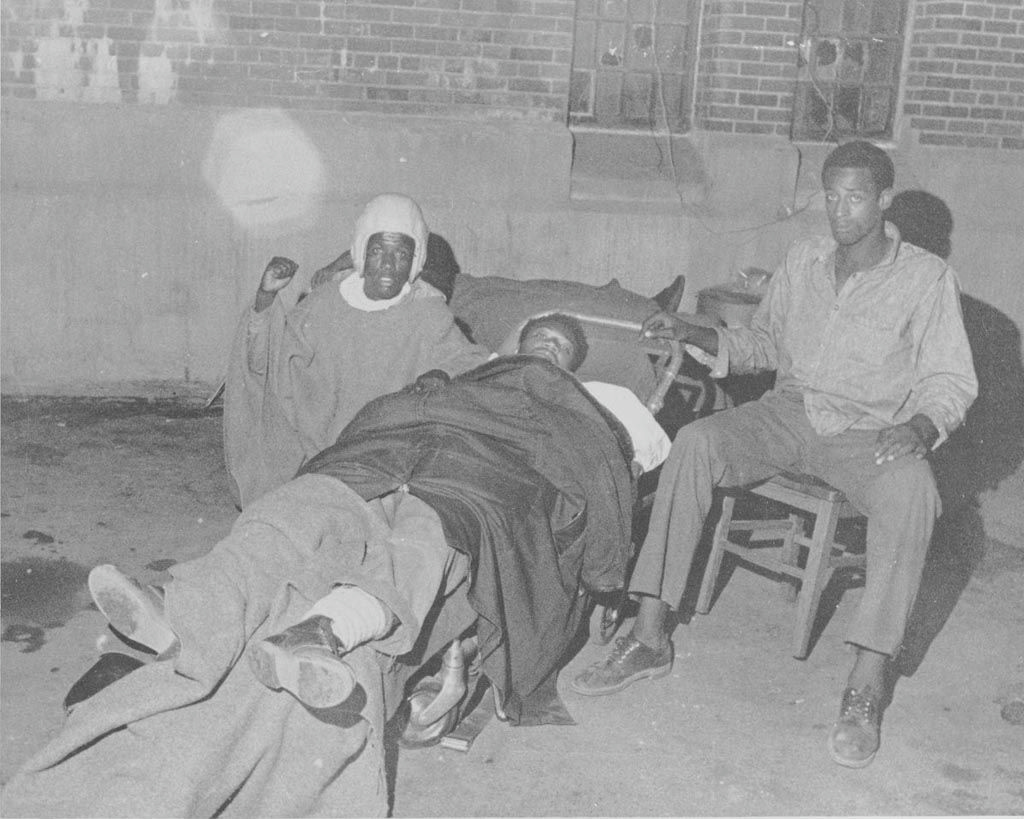

CBC members have been active participants in debates over the best ways to address police brutality through Congressional action. In 2020, for example, the CBC led the introduction of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act in the House of Representatives. Just 9 days later, Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC), a Black member of Congress but not of the CBC, introduced the Just and Unifying Solutions to Invigorate Communities Everywhere Act of 2020 (JUSTICE Act) in the Senate. While the bills addressed some of the same topics, including the use of chokeholds and no-knock warrants; tracking law enforcement misconduct and use of force; and training officers in areas such racial bias, CBC Chair Rep. Karen Bass called the Republican-led Senate bill represented a “watered-down fake reform bill.” CBC members argued the JUSTICE Act was a more limited and less enforceable approach to addressing systemic issues of police brutality and racial injustice because it primarily focused on data collection or incentivizing reforms. The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act passed the House. In the Senate, however, negotiations led by Sen. Scott and CBC member Sen. Cory Booker failed to lead to a compromise between the bills.